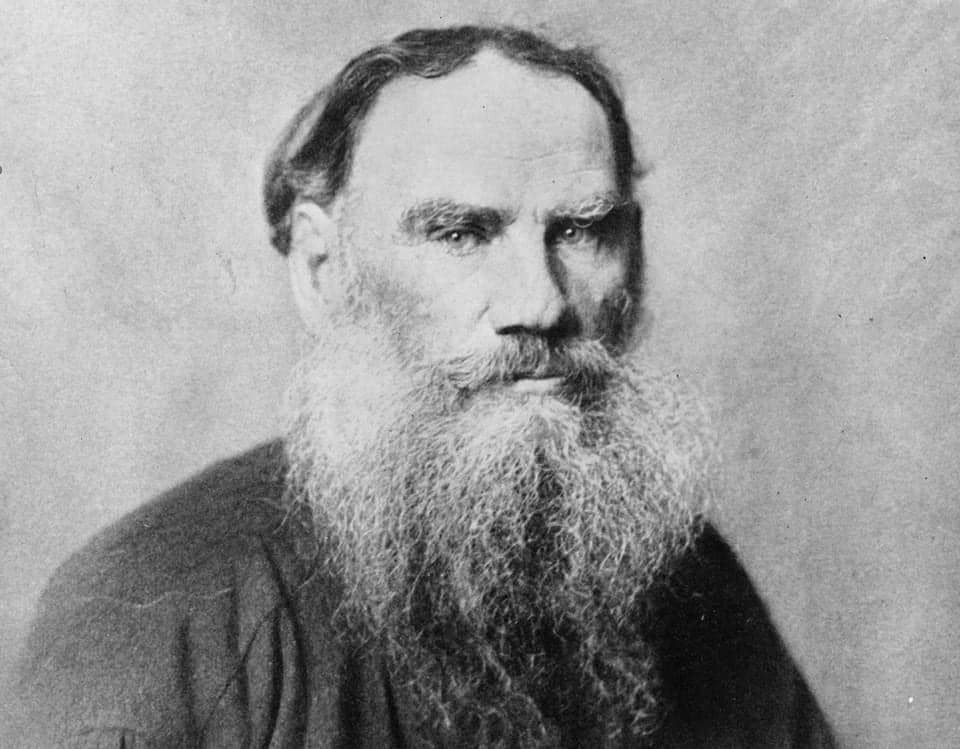

“All happy families are alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.”

― Leo Tolstoy, Anna Karenina

![]()

“All happy families are alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.”

― Leo Tolstoy, Anna Karenina

![]()

“Only to change the world

Everyone is thinking

To change yourself first

No one thinks.”

Leo Tolstoy

![]()

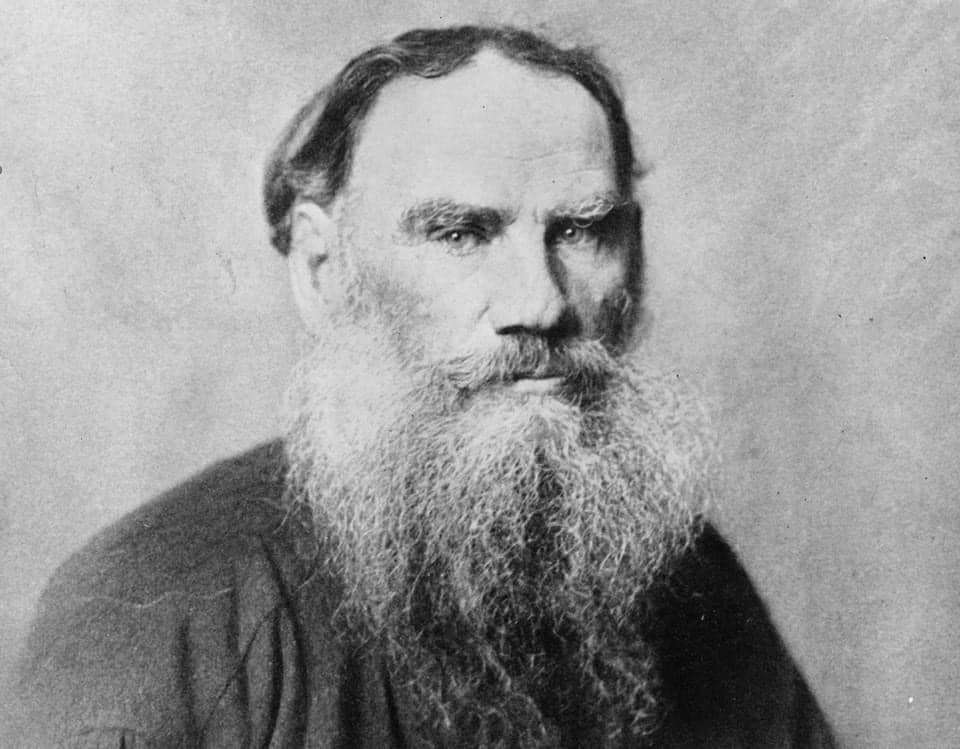

As explained in the book, Culture, Customs and Literature of the Eastern Pwo Karen People in Myanmar, by Ashin Pin Nya Tha Mi (2022), the basic word order for Eastern Pwo Karen is Subject-Verb-Object, whereas the basic word order for Burmese is Subject-Object-Verb. We can see the examples shown below.

‘Uncle eats rice.’

| Subject (ကတ္တား) | Verb (ကြိယာ) | Object (ကံ) |

|---|---|---|

| မင်စဝ် | အင်း | မေဝ် |

| Uncle | eat | rice |

‘ဘကြီးသည် ထမင်းကို စားသည်။’

| ကတ္တား | ကြိယာ | ကံ |

|---|---|---|

| မင်စဝ် | အင်း | မေဝ် |

| ဘကြီး | စားသည် | ထမင်း |

According to the research from Kato (2019), Karenic languages follow the word order of Subject-Verb-Object, unlike the languages of the Tibeto-Burman language family, most of which are Subject-Object-Verb type.

Kato (2019) also cited that the change of Karenic languages from Object-Verb to Verb-Object could have been the result of contact with Mon in the late first millennium AD (700-999 AD).

Examples are shown below.

‘Thawa struck Thakhlein.’

| Subject (ကတ္တား) | Verb (ကြိယာ) | Object (ကံ) |

|---|---|---|

| သာအွာ | ဍောဟ် | သာခၠိင်း |

| Thawa | strike | Thakhlein |

“သာအွာသည် သာခလိင်းကို ရိုက်သည်။”

| ကတ္တား | ကြိယာ | ကံ |

|---|---|---|

| သာအွာ | ဍောဟ် | သာခၠိင်း |

| သာအွာ | ရိုက်သည် | သာခလိင်း |

In the case of a ditransitive verb, the two objects are arranged in the order of Recipient – Theme.

(Kato, 2019, p. 142)

‘Thawa gave Thakhlein a jackfruit.’

| Subject | Verb | Indirect Object | Direct Object |

|---|---|---|---|

| သာအွာ | ဖှ်ေလင့် | သာခၠိင်း | နွဲာသး။ |

| Thawa | give | Thakhlein | jackfruit |

“သာအွာသည် သာခလိုင်းကို ပိန္နဲသီးတစ်လုံး ပေးသည်။”

| ကတ္တား | ကြိယာ | ကံ (Indirect) | ကံ (Direct) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Subject | Verb | Indirect Object | Direct Object |

| သာအွာ | ဖှ်ေလင့် | သာခၠိင်း | နွဲာသး။ |

| သာအွာ | ပေးသည် | သာခလိင်း | ပိန္နဲသီး |

References:

Kato, A. (2019, June 3). Pwo Karen. The Mainland Southeast Asia Linguistic Area, 131–175. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110401981-004

Pin Nya Tha Mi. (2022). Culture, Customs and Literature of the Eastern Pwo Karen People in Myanmar (1st Edition). Sarpay Beikman.

![]()

Explanation in English

(The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism) [1]

Bīja (T. sa bon ས་བོན་; C. zhongzi), literally “seed”, is used in two contexts:

1) “karmic seeds” that ripen upon meeting with appropriate causes and condition;

2) “seed syllables” used as a focus for visualization in tantric practices.

(SuttaCentral — Dictionary)[2]

bīja

Nature and the Environment in Early Buddhism by S. Dhammikabīja

Seed. A seed is a new plant in the form of an embryo. Some of the parts of seeds mentioned in the Tipiṭaka include the husk (thusa), the kernel (miñja), and in the case of germinating seeds, the sprout or shoot (aṅkura). The seeds of certain plants are encased in a pod (sipāṭaka or kuṭṭhilika). In order to germinate a seed has to have an intact casing, be fresh, be unspoiled by wind or heat and be sown in a good field with properly prepared soil AN.i.135. Some seeds have hard shells that crack only if burned and it was noticed that new shoots often appear quickly after a forest fire SN.i.69. The two factors that enable a seed to grow are nutrition from the soil (paṭhavi rasa) and moisture SN.i.134. Whether the leaves or fruit of the plant is sweet or bitter was believed to depend not on the nutrition but on the nature of the seed AN.i.32. Commenting on the endless cycle of agriculture the monk Kāḷudāyin said: “Again and again they sow the seed; again and again the god king rains; again and again farmers plough the fields; again and yet again the country has grain” Thag.532. The seven types of edible seeds usually mentioned in the Tipiṭaka are sāli, vīhi, mugga, māsa, tila and taṇḍula MN.i.457. Elsewhere, the first two of these are included in a list of edible grains Vin.iv.264. See Dhañña.

(Wikipedia) [3]

In Hinduism and Buddhism, the Sanskrit term Bīja (बीज) (Jp. 種子 shuji) (Chinese 种子 zhǒng zǐ), literally seed, is used as a metaphor for the origin or cause of things and cognate with bindu.

Explanation in Burmese [4][5]

၁ – မူလဗီဇ=အမြစ်မျိုး။

၂ – ခန္ဓဗီဇ=အပင်မျိုး။

၃ – ဖလုဗီဇ=အဆစ်မျိုး။

၄ – အဂ္ဂဗီဇ=အညွန့်မျိုး။

၅ – ဗီဇ ဗီဇ=အစေ့မျိုး။

(မူလပဏ္ဏာသ)

Pali Word Grammar from Pali Myanmar Dictionary [6]

bījagga:bījagga(na)

ဗီဇဂ္ဂ(န)

[bīja+agga]

[ဗီဇ+အဂ္ဂ]

Tipiṭaka Pāḷi-Myanmar Dictionary တိပိဋက-ပါဠိမြန်မာ အဘိဓာန် [6]

bījagga:ဗီဇဂ္ဂ(န)

[ဗီဇ+အဂ္ဂ]

မျိုးစေ့ဦး (အလှူ)။

[Volunteer needed for Eastern Pwo Karen translation for this post]

[ဤအကြောင်းအရာအား အရှေ့ပိုးကရင်ဘာသာစကားသို့ ပြန်ဆိုရန် စေတနာ့ဝန်ထမ်းအလိုရှိသည်။]

Directly extracted from the following sources:

![]()

Explanation in English [1][2]

Four forms of birth

In traditional Buddhist thought, there are four forms of birth:

Explanation in Chinese [3]

四生

154. 金剛經與其它經典常提到『四生』,不知四生是何意義?

四生(梵語catasro-yonayan),(巴利語catasso-yoniyo)。指三界六道有情產生之四種類別。

據俱舍論卷八所載,即:

一、卵生(梵語andaja-yoni,巴利語亦同),由卵殼出生者稱為卵生。如鴨、孔雀、雞、蛇、魚、鳥類、蟻等。

二、胎生(梵語jarayuja-yoni, 巴利語jalabu-ja),又作腹生。從母胎而出生者,稱為胎生,如人、象、馬、牛、豬、羊、驢等。

三、濕生(梵語samsvedaja-yoni,巴利語samseds-ja),又作因緣生,寒熱和合生。即由糞聚、注道、穢廁、腐肉,叢草等潤濕地之濕氣所產生者,稱為濕生。如飛蛾、蚊蚰、蠓蚋、麻生蟲等。

四、化生(梵語upapaduka-yoni,巴利語opaptika),無所託而忽有,稱為化生。如諸天、地獄、中有之有情,皆由其過去之業力而化生。以上四生,以化生之眾生為最多。

Explanation in Burmese [4]

သန္ဓေလေးမျိုး

ဘဝတခုတွင် အစစွာ ဖြစ်ခြင်းလေးမျိုးသန္ဓေဆိုသည်မှာ ဘဝတခုတွင် အစစွာဖြစ်ခြင်းကိုဆိုသည်။ သန္ဓေသည် သံသေဒဇ၊ ဩပပါတိက၊ အဏ္ဍဇ၊ ဂဗ္ဘသေယျက ဟူ၍လေးမျိုးဖြစ်သည်။ လူတို့သည် အမိပမ်းတွင်း၌ ကိန်းအောင်း နေရသောကြောင့် ဂဗ္ဘသေယျကအကြောင်း အထူး လေ့လာသင့်ပေသည်။ သန္ဓေလေးမျိုးကိုရေးသားရာ၌ ဇလာဗုဇအစားအခေါ်များအသိများသော ဂဗ္ဘသေယျကကိုသုံးစွဲမည်။

သန္ဓေဆိုသည်မှာ တစ်ဘဝနှင့် တစ်ဘဝ ဆက်စပ်ခြင်း၊တစ်နည်း ဘဝတစ်ခုတွင်အစစွာ ဖြစ်ခြင်းကိုဆိုသည်။ တရားကိုယ်မှာသက်ရှိသတ္တဝါ၏ နာမ်တရားနှင့်ရုပ်တရားပင်တည်း။ ယင်းသန္ဓေကို ပဋိသန္ဓေ ဟူ၍ပါဠိဘာသာ၌ ခေါ်ဝေါ်သုံးစွဲကြသေးသည်။ ထိုသန္ဓေသည် (၁)သံသေဒဇ၊ (၂) ဩပပါတိက၊ (၃) အဏ္ဍဇ၊ (၄) ဇလာဗုဇဟူ၍ လေးမျိုးဖြစ်သည်။ ဇလာဗုဇကိုအမိဝမ်းတွင်း၌ ကိန်းအောင်းနေရသောကြောင့် ဂဗ္ဘသေယျကဟုလည်းခေါ်ဆိုသည်။

၁။ အဏ္ဍဇဆိုသည်မှာ ဥ၌ ဖြစ်သောပဋိသန္ဓေကိုဆိုသည်။ (Oviparity)

၂။ ဂဗ္ဘသေယျကဆိုသည်မှာ အမိဝမ်း၌ကိန်းအောင်း၍တည်ရသောပဋိသန္ဓေကိုဆိုသည်။ (Viviparity)

၃။ သံသေဒဇဆိုသည်မှာ – သစ်ပင်၊ ပန်းပင်၊ နွယ်ပင်၊ မစင်၊ ကျင်ကြီး၊ ကျင်ငယ်၊ ရေပုပ်၊ ရေသိုးစသော အညစ်အကြေး၌ဖြစ်သော ပဋိသန္ဓေကိုဆိုသည်။ (Wet Birth)

၄။ ဩပပါတိက ဆိုသည်မှာ ဘုံ၊ ဗိမာန်၊ ဥယျာဉ်၊ ရေကန်စသောဌာနတို့၌ဖြစ်သော ပဋိသန္ဓေကိုဆိုသည်။ (Metamorphosis (Biological)/ Metaplasia)

[Volunteer needed for Eastern Pwo Karen translation for this post]

[ဤအကြောင်းအရာအား အရှေ့ပိုးကရင်ဘာသာစကားသို့ ပြန်ဆိုရန် စေတနာ့ဝန်ထမ်းအလိုရှိသည်။]

Directly extracted from the following references:

![]()

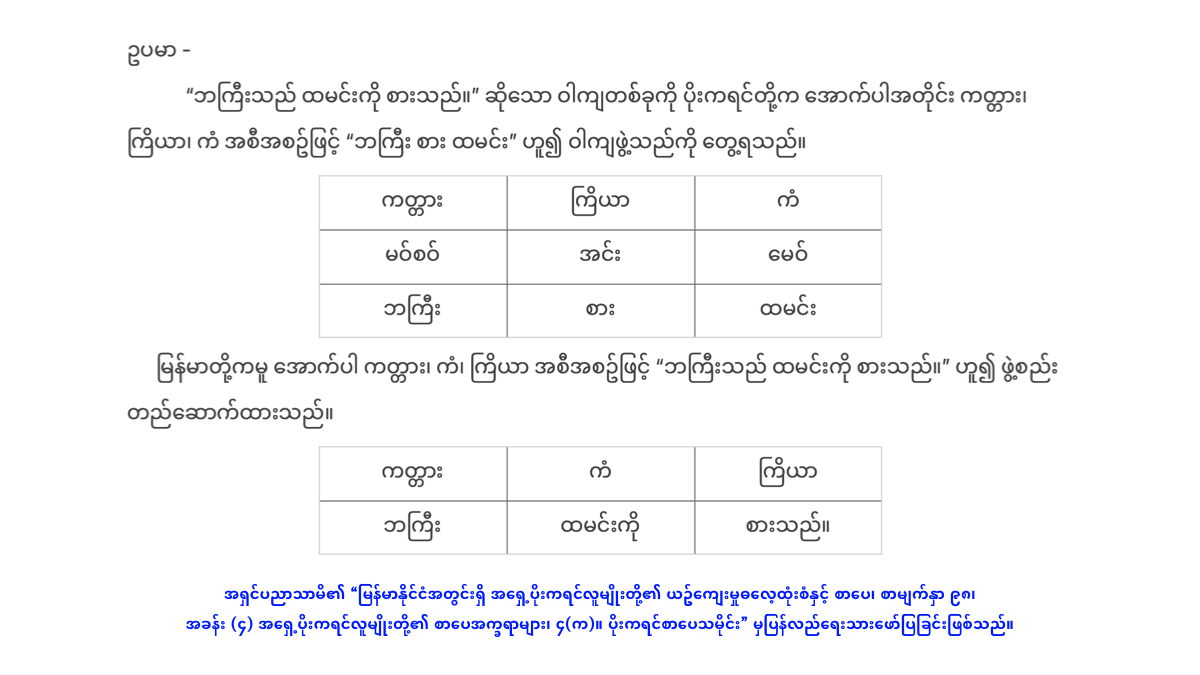

Oddly, after his family situation had disintegrated, Alexander’s life seemed to improve immensely. His experience as bookkeeper in his mother’s store landed him a job as a clerk with the international trading firm of Nicholas Cruger, a New Yorker whose business hub was on St. Croix.

The boy’s exceptional skills and endless learning capacity soon saw him running the firm upon the owner’s absence. As a teenager, Hamilton was inspecting cargoes, advising ships’ captains, and preparing bills of lading. Under Cruger’s tutelage, Hamilton mastered the intricacies of global finance and experienced first hand how the material interests of peoples and countries interwove in the complicated fabric of international trade. The bustling port of St. Croix, which was a melting pot of residents and visitors from all over the world, early formed a picture of a global village in Hamilton’s mind. He also saw the darker side of international dealings, as the island was a center for the slave trade. Hamilton came away with a deep hatred of slavery, and he eventually co-founded an abolitionist society in New York. In the meantime, the youngster drank in everything he saw. Nothing Hamilton experienced ever went unused.

Whereas Nicholas Cruger exposed Alexander Hamilton to material realities, the Reverend Hugh Knox provided him with a strong spiritual and intellectual grounding. Knox–who took Hamilton under his wing shortly after Rachel’s death–was a Scottish Presbyterian minister at odds with the mainstream of his faith because of his firm belief in free will over the Calvinist doctrine of Predestination. For someone like Hamilton who was otherwise predestined to a life of obscurity, we can see how Knox’s philosophy would have appealed to him. The Reverend’s encouragement and influence undoubtedly led Hamilton to dream big dreams. Knox, a brilliant sermon-writer and occasional doctor, took the young orphan under his wing and tutored him in the humanities and sciences. When he was able to get away from the office, Hamilton further expanded his intellect in Knox’s library, where he read voluminously in the classics, literature, and history. Hamilton, who had early fancied himself a writer, published an occasional poem in the local paper, and impressed the residents of the island with a particularly vivid and florid account of a hurricane in 1772.

By 1773, his mentors had raised enough money to send him to America to continue his education. It was clear to all who encountered the young man that he was much too brilliant and determined to remain in what Hamilton himself termed “the grovelling condition of a clerk.” Cruger, Knox, and other wealthy islanders, sent Hamilton off in June of 1773 to New York to study medicine, most likely in the hope that he would return to the island and set up his practice there. But Alexander Hamilton was never to see the West Indies again.

Featured image: John Trumbull, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

![]()

Qiu Chuji (丘處機) (Born 1148 in Chi-hsia, China — Died July, 1227 in Beijing, china), widely known by his Taoist name Chang Chun Zi (長春子), was a Taoist master who provided spiritual guidance to Genghis Khan and was appointed by him as the head of religious affairs in China. His journey from northern China to Afghanistan to meet Genghis Khan was recorded by his disciple Li Chih-Ch’ang and contains some of his dialogues with Genghis Khan. Besides his involvement with Genghis Khan, and politics, Qiu Chuji was one of the most major Taoist spiritual leaders in history. Qiu Chuji was a disciple of Wang Chongyang, the founder of the Quanzhen (Complete Reality) school. Qiu Chuji is at the origin of his own branch of Quanzhen Taoism called Dragon Gate.

Journey to Genghis Khan

Around 1219, Genghis Khan summoned Qui Chuji to come visit him. Genghis Khan was principally interested in extending his life, since he had heard talk of Qui Chuji’s abilities in this regard. Qui Chuji was located in Lai-chou in northern China when he received the summons. He tried to arrange for Genghis to visit him when he returned from his campaign in the West (Central Asia and Afghanistan), but to no avail. Qui Chuji received a letter from Genghis that highly praised him and Taoism, and implored him to come to Central Asia.

In 1221, Qiu Chuji set out on his journey. He first responded to a request to visit Genghis’s brother Temuge, who was interested in extending his life. Qui Chuji told him that these matters could only be explained to someone who fasted and observed certain rules. Then Temuge sent him on his way, with a request for him to return after he had seen Genghis.

During the journey, Qiu Chuji was treated well but not always given what he wanted; for example he was not allowed to stop and rest for the winter. When Genghis’s son Chaghatai invited Qiu Chuji to stay with him to the south of the Amu Darya, Qiu Chuji refused because he thought his vegetarian diet was not viable in that area. Qiu Chuji received a letter from Genghis, who was on his way back to the East and eager to meet the master.

Genghis met qui Chuji near the Amu Darya. According Arthur Waley’s translation of the Travels of an Alchemist, Genghis said, “Other rulers summoned you, but you would not go to them. And now you have come ten thousand li to see me. I take this as a high compliment.”

Qiu Chuji replied, “That I, a hermit of the mountains, should come at your Majesty’s bidding was the will of Heaven.”

Genghis asked, “Adept, what medicine of long life have you brought me from afar?”

Qiu Chuji replied, “I have means of protecting life, but no elixir that will prolong it.”

Genghis was curious and Qiu Chuji answered his questions, teaching him about Taoism. They had many meetings, which were attended by interpreters and two of the Mongol leaders who had brought Qui Chuji to Genghis. Genghis invited Qiu Chuji to have all his meals with Genghis, but Qiu Chuji declined because he wanted peace and quiet. Genghis was so pleased with Qiu Chuji’s teachings that he ordered for them to be written down in Chinese characters.

In a sermon that has come down to us under the name Hsüan Fēng Ch’ing Hui Lu, Qui Chuji advised Genghis to practice chastity and vegetarianism. Genghis took this advice to heart and tried to apply it to some extent. Qiu Chuji also gave him political advice: he told Genghis not temporarily avoid taxing some provinces so they could economically recover from the effects of war. He advised having a Chinese minister manage this, and pointed out that this method had worked well for the previous dynasty.

Genghis and Qui Chuji returned to Mongolia together. They continued to meet and talk throughout the journey. Qiu Chuji did what he could to save lives by feeding the destitute. He convinced Genghis to hunt and eat meat less, and Genghis stopped hunting for two whole months. As a farewell gift, Genghis exempted the master’s pupils from taxation.

After Genghis and Qiu Chuji separated, Genghis continued to write to him. He wrote (in Arthur Waley’s translation ) “I am always thinking of you and I hope you do not forget me.” He requested for Qui Chuji and his disciples to pray for his longevity, and he offered to let Qiu Chuji live wherever he wanted.

Qiu Chuji died on July 23, 1227. Genghis Khan died a month later. Qui Chuji left behind many disciples, poetry, and some of his sermons which were recorded. His Dragon Gate school benefited from Genghis Khan’s support and became the dominant branch of Taoism.

Quotes

“Sweep, sweep, sweep! Sweep clear the heart till there is nothing left. He with a heart that is clean-swept is called a ‘good man.’”

“For ten thousand li I have rode on a Government horse; It is three years since I parted from my friends. The weapons of war are still not at rest, but of the Tao and its workings I have had my chance to preach.”

“Those who study Tao must learn not to desire the things that other men desire, not to live in places where other men live. They must do without pleasant sounds and sights, and get their pleasure only out of purity and quiet.”

References

The Travels of an Alchemist (1931), by Li Chih-Ch’ang, tr. Arthur Waley

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Chang-chun

https://www.revolvy.com/main/index.php?s=Dragon+Gate+Taoism&item_type=topic

Extracted from https://medium.com/@longlivearth/qiu-chuji-guru-of-genghis-khan-7b570973dad0

Originally published at www.longlivearth.com on July 23, 2018.

Feature image: The “Love” Story between Genghis Khan VS Taoism Master Qiu Chuji | Witch From Far East (wordpress.com)

Article originally published by LLE staff Taifun33 on the decentralized blockchain encyclopedia Lunyr. Free to modify and distribute under the Creative Commons 4.0 License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

![]()